Finding out why this happens was the task of Victoria (Shu)Zhang, Aharon Cohen Mohliver, and Marissa King in research published in Administrative Science Quarterly. To get to the core of the problem, the

researchers made two important innovations. The first innovation was to look

carefully at how doctors are connected to each other through their patient

sharing. Patient sharing means that the same patients see more than one doctor

and implies that the doctors can communicate and learn from each other. Through

their network of patient-sharing peer doctors, they can learn how to follow

good practice, or they can learn how to deviate from it.

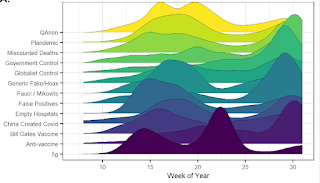

The second innovation was to distinguish deviant (illegal)

over-prescription from marginal over-prescription. Marginal over-prescription

is when the doctor prescribes too much according to good practice, but not so

much that it clearly violates legal limits. This is a liminal (borderline)

practice, and accounts for more over-prescription than deviant

over-prescription. Much more: 56 percent is liminal, as opposed to 9 percent

deviant. The rest is by doctors who cannot be easily classified as either

deviant or liminal.

So how do doctors learn from their network? The answers are

disturbing. Any kind of over-prescribing in the network (liminal or deviant)

encourages any kind of over-prescribing by the doctor (liminal or deviant).

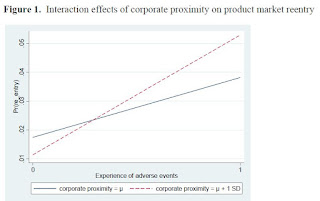

Network misconduct promotes physician misconduct. So what distinguishes between

doctors engaging in one or the other of these types of over-prescribing? It

turns out that doctors with a central position (many connected peers) or a

cohesive position (connected peers are connected to each other) were more

likely to engage in deviant, criminal over-prescription. Looser connected

network positions encouraged liminal over-prescription.

What about doctors being more or less honest? We often think

of people as being different in integrity and willingness to violate norms and

break laws. We may even imagine that people differ in their tendencies to build

networks depending on who they are. Part of the strength of this research is

how carefully the researchers examined this explanation, finding that the

network had strong effects even when accounting for many alternative

explanations.

Which is not to say that doctor differences don’t exist. In

fact, high workloads led to much more liminal over-prescription but only a minor

increase in deviant over-prescription. Illegal prescription was mostly related

to age – young doctors or doctors near retirement age were more likely to do

it.

These are disturbing answers because they show that laws and

norms are not enough. Laws regulate deviant/illegal over-prescription, but that

accounts for a minority of the dangerous prescription. Norms are learnt, but

findings on network effects show that the physicians learn liminal

over-prescription just as well as normative best practice. And here is the most

worrying part of the research, which I did not write until now. The

patient-sharing networks the researchers measured were not captured through

shared prescription of benzodiazepines or any other mental health drug—only

regular drugs. This research shows that networks not organized around

misconduct can produce misconduct learning.