We all try to learn from our failures, and we believe that we usually do so successfully. Similarly, we often think that firms can learn from failures, and this belief is shared by people who observe (and work in) firms and those who study organizational learning. It may be shocking to realize that some of the details on whether and how firms learn are not well documented. For example, we know that firms will change something after experiencing failure, but we are rarely able to measure whether they change the right thing and whether the change is an improvement.

This is why research by Cheon Mok (John)Kim, Colleen M Cunningham, and John Joseph published in Academy of Management Journal is interesting. They checked whether medical device firms could distinguish between failures caused by product features or market conditions and found

that they could. So far so good. They also checked whether failures due to product features led

to re-entry with a new product, and this is where things got more complicated –

and interesting.

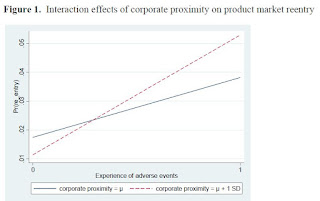

In fact, the findings were even stronger

for the more repairable types of failures. If the failure was distinctly from

the product design, not the user, then corporate proximity had greater effect. If

the product failure was severe, then corporate proximity had greater effect. In

both cases, the fault is more obvious and more easily traced to the firm, and

accordingly it should be easier to learn from failure. And learn they did.

This is important knowledge for two

reasons. First, although we often assume that learning from failure happens, it

is often the case that the very things we assume to be true are faulty in some way,

and need to be checked carefully. That is also true about learning from failure,

because the conditions that make it happen are not always present. The firm

with highly decentralized management that is also geographically dispersed and

diversified has three strikes against learning from failure. There are many

such firms.

This brings us to the second point. From

what we know about learning, we should also be able to design organizations that

learn well. Given how learning is related to connections within the firm, and

the attention (and surveillance, support, and resources) that follows, designing

firms with structures that fail to learn is a completely unnecessary error, especially given

the costs of simply giving up when re-entry with an improved product would have

been possible.

If we know how firms learn, we can design

them to learn well.